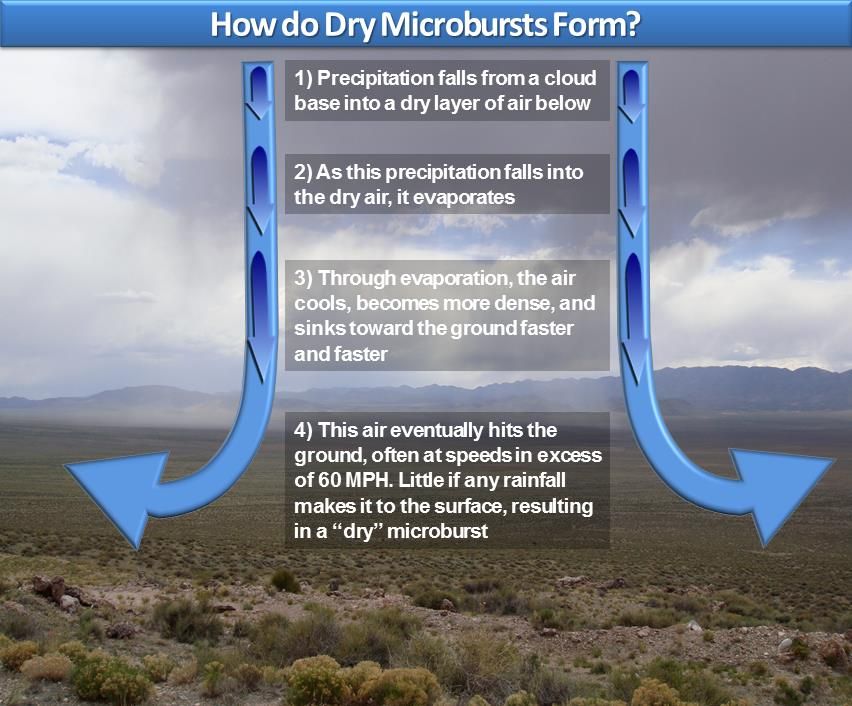

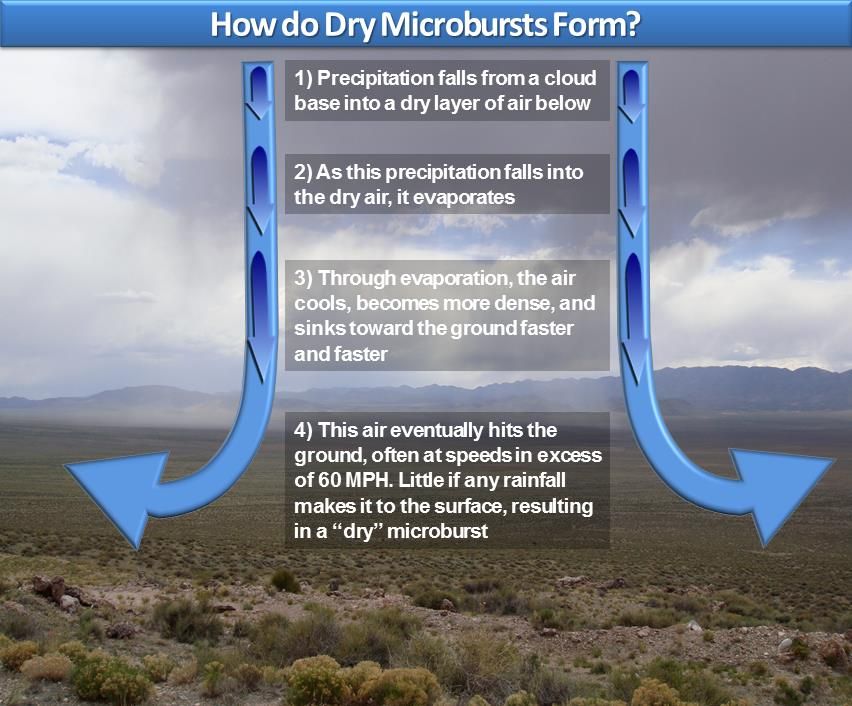

How do dry microbursts form?

Years ago we lost a good friend to this type of wind.

Keep an eye to the sky, live to ride another day.

The Microburst

By Jim S

Schematic of the Traveling Microburst (Fujita 1981)

Yesterday evening I was working on my computer at home when the Emergency Broadcast System alarm went off on the TV in the adjoining room. It really got my attention since I wasn't expecting much in the way of severe weather, so I thought it was either an Amber alert or perhaps something more serious. I walked over to where I could see the TV and noticed it was a severe thunderstorm warning issued for Salt Lake and Davis County.

The culprit was a microburst, a localized downburst that produces strong straight line winds at the ground as depicted above. The one we had last night was an example of a dry microburst as most of the precipitation that generated it evaporated before reaching the ground. Some meteorologists differentiate between microbursts and macrobursts depending on the size of the area affected. Indeed, this event may have had macroburst scale, but we will stick with microburst for this discussion.

Dry microbursts are typically generated in Utah by high based storms. Precipitation falling from these storms falls into the dry low-level airmass and evaporates, with the resulting cooling generating an area of locally cool, dense air that sinks very rapidly towards the ground. Environmental conditions were ripe for microburst generation last night with an extremely deep, dry boundary layer extending from the surface to near 500 mb.

Meteorologists use a variable known as Downward Convective Available Potential Energy (DCAPE) to assess the potential strength of downdrafts and downbursts. Last night, the DCAPE was 1684 joules/kg, which is a very high value indicating the potential for downburst-related strong winds. What was needed was some precipitation to get things going.

The curious thing about last nights storm is that it barely showed up on the lowest elevation radar scan that we normally use to examine precipitation (especially in the winter). It was best picked up by the so-called "third tilt", which is at 1.3º relative to the local horizon. Even still, the storm was pretty unimpressive with relatively weak radar reflectivities.

But, the key here was the evaporation of that light precipitation into the dry airmass. And, it led to very strong winds. Here are some storm reports issued by the NWS, which include a 75 mph wind gust. I saw one house on the news with a very large tree on it. The residents of that home were very fortunate that it was well constructed!

Keep an eye to the sky, live to ride another day.

The Microburst

By Jim S

Schematic of the Traveling Microburst (Fujita 1981)

Yesterday evening I was working on my computer at home when the Emergency Broadcast System alarm went off on the TV in the adjoining room. It really got my attention since I wasn't expecting much in the way of severe weather, so I thought it was either an Amber alert or perhaps something more serious. I walked over to where I could see the TV and noticed it was a severe thunderstorm warning issued for Salt Lake and Davis County.

The culprit was a microburst, a localized downburst that produces strong straight line winds at the ground as depicted above. The one we had last night was an example of a dry microburst as most of the precipitation that generated it evaporated before reaching the ground. Some meteorologists differentiate between microbursts and macrobursts depending on the size of the area affected. Indeed, this event may have had macroburst scale, but we will stick with microburst for this discussion.

Dry microbursts are typically generated in Utah by high based storms. Precipitation falling from these storms falls into the dry low-level airmass and evaporates, with the resulting cooling generating an area of locally cool, dense air that sinks very rapidly towards the ground. Environmental conditions were ripe for microburst generation last night with an extremely deep, dry boundary layer extending from the surface to near 500 mb.

Meteorologists use a variable known as Downward Convective Available Potential Energy (DCAPE) to assess the potential strength of downdrafts and downbursts. Last night, the DCAPE was 1684 joules/kg, which is a very high value indicating the potential for downburst-related strong winds. What was needed was some precipitation to get things going.

The curious thing about last nights storm is that it barely showed up on the lowest elevation radar scan that we normally use to examine precipitation (especially in the winter). It was best picked up by the so-called "third tilt", which is at 1.3º relative to the local horizon. Even still, the storm was pretty unimpressive with relatively weak radar reflectivities.

But, the key here was the evaporation of that light precipitation into the dry airmass. And, it led to very strong winds. Here are some storm reports issued by the NWS, which include a 75 mph wind gust. I saw one house on the news with a very large tree on it. The residents of that home were very fortunate that it was well constructed!